Source: Financial Times

For us, at Holden & Partners, impact investment is not only about identifying environmental, social, or governance (ESG) challenges and analysing how an investment may capitalise upon them to generate a sustainable business advantage; it also entails a commitment to measure and to manage the impact of those environmental and social effects. At the same time, impact investments must provide a risk-adjusted market rate of return. Both compelling financial performance and a verifiable impact should take equal weight.

It is in this respect that impact investment differs from broader sustainable investment initiatives, which use an assessment of ESG factors to analyse the ability of companies to ensure the longevity of their products and business models; or thematic investment, which identifies global macroeconomic themes and seeks out opportunities which are best-placed to capitalise upon them. Impact investing, unlike the responsible investment strategies that came before it, attempts to combine a direct and tangible social or environmental outcome with financial return. It is not a question of whether one strategy is superior to the other, but a case of recognising that they are all an extension of the same philosophy: namely that considering a wider range of issues than financial metrics to assess potential returns facilitates investment in a way that acknowledges future threats, and takes advantage of unrealised opportunities.

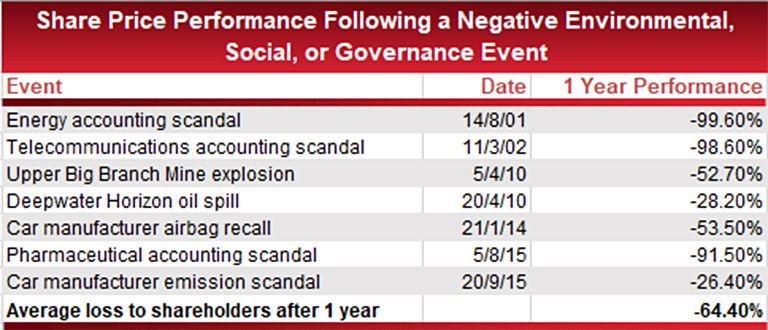

Holden & Partners has long been an advocate of this type of investment process in generating superior long-term growth and mitigating risk. The table below provides a reminder of issues that may occur when investors take a short-term approach and disregard environmental, social, and governance factors; in the aftermath of an unfavourable event, the resulting share price movements can be stark. Regardless of whether an investor is following a sustainable, thematic, or impact investment approach, these are the risks that they attempt to avoid.

Source: Morgan Stanley Investment Management, ESG and the Sustainability of Competitive Advantage. Share price data taken from Bloomberg, as at November 2016. Past Performance is no guarantee of future results.

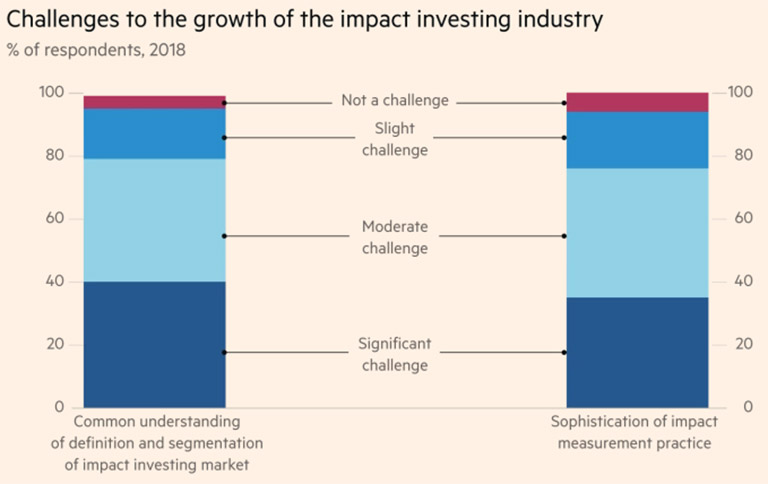

The measurement of impact is therefore what sets the industry apart from more well-established sustainable investment styles, but the complex and inaccurate nature of those measurements is another problem plaguing the sector. In theory, a manager could take several approaches: analyse a portfolio’s carbon footprint and establish the amount of greenhouse gases avoided; calculate the output of renewable energy generated; assess the volume of water saved, treated, or provided; compute the weight of waste treated and material recycled; or evaluate the number of new jobs created. In reality, however, these measurements are often impractical to obtain. Even more difficult to establish is whether an impact is material relative to the size of a specific investment, or to the size of an investor’s total portfolio.

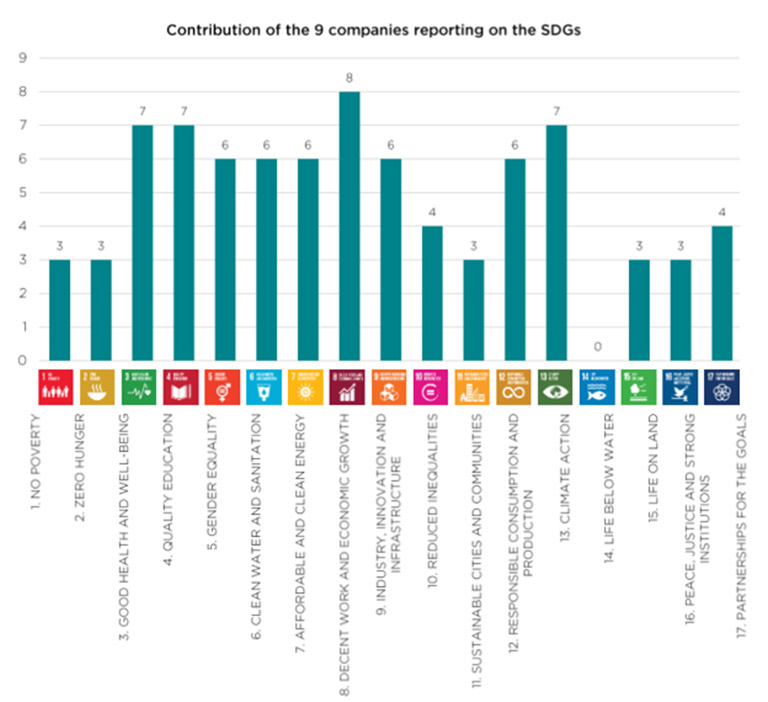

In recognition of this, some managers have taken to measuring their impact or constructing an investment framework with reference to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – a set of 17 targets intended to address global challenges and “end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all”5. This, too, is not without its drawbacks. Although the goals highlight many systemic global issues that sustainable investors seek to address in their allocation of capital, they are extremely far-reaching and intended more for use in informing government and supranational policy, than stipulating a framework for business investment. The lack of available data on which to base an assessment of the contribution of a company to each goal, and the consistency of that data, means that investment models based on the impact of the SDGs are susceptible to manipulation.

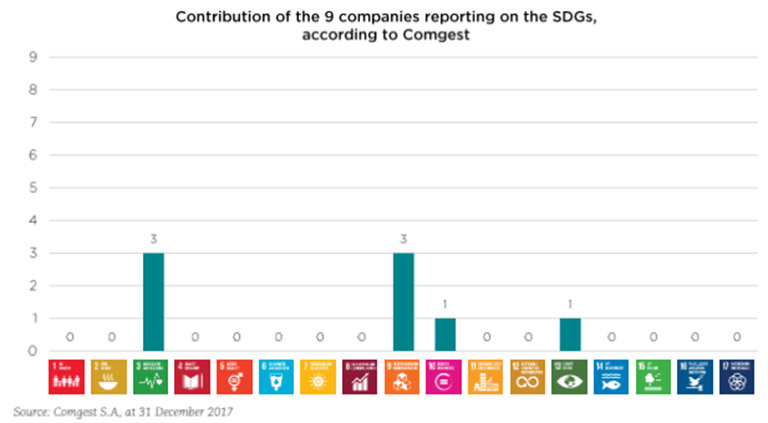

An assessment by international asset manager, Comgest, on how corporate disclosure on impact and contribution to the SDGs may differ from reality yielded the following results: for the 9 companies reporting on their contribution to society and alignment with the SDGs, the collective impact was far lower than the information provided by the firms themselves would lead investors to believe.6 Such is the risk of using broad definitions of impact. Whole sectors, such as the large pharmaceutical firms, could be classified as appropriate ‘impact’ investments due to their correlation with SDG number 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing), but categorisations of this nature are questionable, misinterpret the true impact of certain areas on society, and are unlikely to provide the outcomes investors expect. Assessing impact simply through a company’s adherence to the SDGs may, therefore, be insufficient.

Source: Comgest S.A, companies’ annual reports and CSR/sustainable development reports at 31 December 2017

Source: Comgest S.A, at 31 December 2017

Despite this, the growth in impact investment ultimately represents a favourable development in the expansion of the sustainable investment industry. At Holden & Partners, we incorporate funds investing in impact assets into our ethical, sustainable, and thematic (EST) investment proposition. The objectives of these model portfolios is not only to generate long-term, sustainable returns and mitigate risk, but also to deliver positive societal change.

An increasing number of market participants are cognisant of the benefits of heeding social and environmental impact and recognise that the emphasis placed on these considerations can offer a valuable insight into the quality of a company’s management, culture, and risk profile. This number will only grow as the millennial generation, who place a high level of importance on corporate responsibility, acquire greater levels of wealth. The issues of undeveloped measurement practices and questionable definitions may continue to be problematic in the short-term but, with awareness of these issues, careful due diligence, and professional scepticism, investors can achieve the tangible outcomes they desire – a financial return and positive impact that benefits not only the investment industry, but business and society as a whole.

1 gsgii.org/year/2018

2 https://thegiin.org/research/publication/annualsurvey2017

3 https://www.ft.com/content/f361cf1d-1480-353d-85cb-aab7ed6a2e5e

4 https://www.ussif.org/files/Publications/GSIA_Review2016.pdf

5 https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/

6 Global Emerging Markets Equity Strategy, Article 173 Report – 2017, Comgest